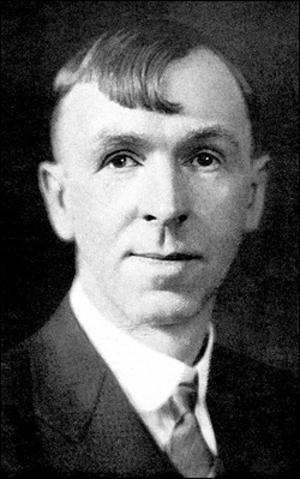

HARRY STEPHEN KEELER!

|

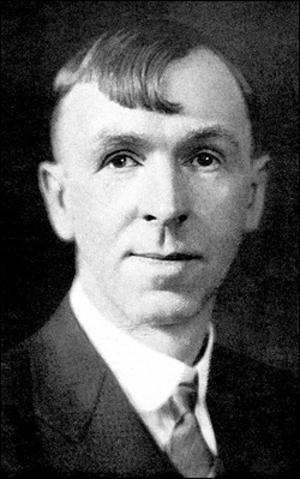

I came fairly late in

life

to an appreciation of the unique author Harry Stephen Keeler (1890 –

1967); I heard

about him at various times over the years, but never found any of his

works in used

bookstores. It's difficult to know where to begin in discussing Keeler.

He started writing

and placing stories in

pulps and poverty-row slicks in about 1905, while still a teenager. He

got a degree

in Electrical Engineering from what is now Illinois Institute of

Technology, and much

accurate or plausible discussion of technology appears in his later

novels. His mother

ran a boarding house catering to the theatrical trade, and a

fascination with acting, various kinds of stage acts, carnivals and

circus freaks is obvious in his literary output.

For reasons unknown, Keeler's mother placed him in an insane asylum

briefly

around 1910; he wasn't there long, but he left with a contempt for the

psychiatric profession

which shows up clearly in his novels, where when any “expert opinion”

is

sought from one psychiatrist, a completely opposite opinion is

invariably obtained from another.

His close encounter with those who were genuinely mentally ill also

left marks that

are seen very often in his writing, particularly in his clinical and

non-committal depictions

of various psychopathic characters. There are a large number of

constantly recurring themes in

his fiction, including human skulls, insurance frauds, pulp magazines,

crooked lawyers, Siamese twins, eccentric wills, prisoners awaiting

execution, 1920s-1930s newspaper journalism [he was the editor of

weekly newspaper The Chicago Ledger from 1919 to 1923], secret codes, optometry,

dentistry, drugs with strange effects on mind and behavior, physical

anthropology, bizarre dialects,

accents and slang, acquisition and trading of stocks to gain control of

a corporation,

stock swindles and all kinds of con-games [Keeler was a personal friend of

famous con-man Joe “Yellow Kid” Weil], Chinese laundries, circuses

and carnivals, the

unexpected death of a key character in the very

midst of the action, various kinds of appeals to the radio

listening audience in the midst of a very popular regularly-scheduled

broadcast, the city of Chicago (where Keeler was born and lived out his

life) and often-little-appreciated peculiarities of the human

anatomy.

|

The total number of different novels

written by Keeler in his

career is difficult to estimate, because of his breaking of long novels

into sub-novels that were published individually, and his re-use of

material, particularly early short

stories... but somewhere around 85 seems correct. His first novels

appeared in print

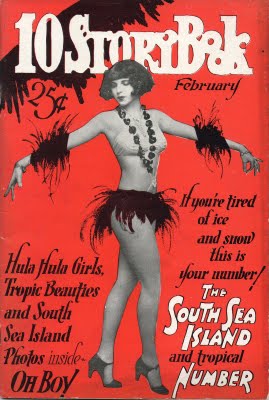

around 1924. From 1916 to 1941 he served as the editor of a

poverty-row pulp,

Ten Story Book. This magazine featured short general

fiction and serialized novels, but evolved to feature pin-up photos,

cartoons, fiction and articles that would be considered titillating for

the day. Despite the contents

of his magazine, Keeler's own fiction, throughout his career,

invariably avoided

the slightest hint of sex or hanky-panky. Keeler boys and girls

invariably fall

in love at first sight, and their only concern thereafter is getting

married

or obtaining permission to wed from some ogre-like parential figure.

It's a bit

rare for Keeler lovers even to kiss, on or between pages. Keeler also

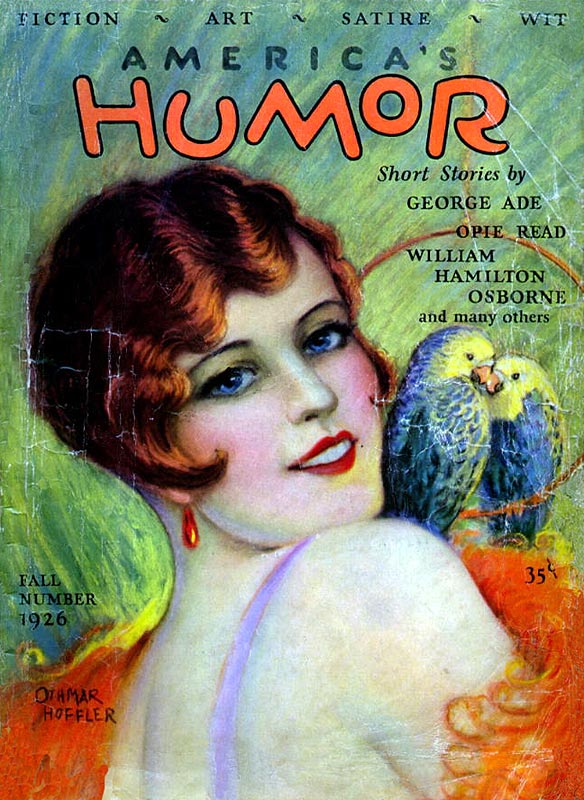

edited America's Humor, a low-end imitation of the more popular

College Humor magazine, and a number of other small-circulation pulps based in Chicago. Keeler's very keen sense of humor is

on prominent display in all his novels, particularly in character names.

|

|

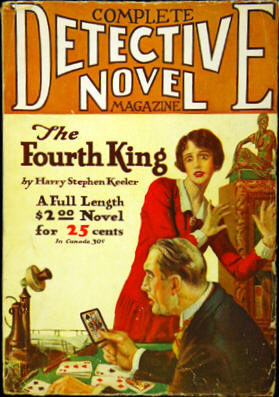

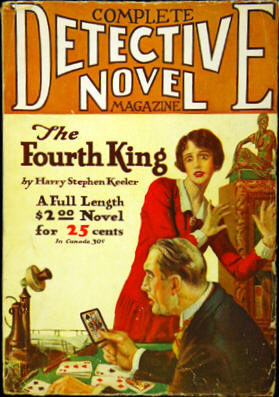

Keeler's early novels come close to being conventional

mysteries [The Fourth King (1929) being a typical example], but from almost

the beginning of his professional writing career he was fascinated by the so-called

“web-work plot,” in which a large number of characters, incidents and

situations develop roughly in parallel, with the parallel storylines intersecting at

various unlikely points, until central questions raised during the course of the novel,

such as the identity of a killer or the whereabouts of a missing person, are answered

at the last possible moment, with the solution often involving a plot thread which has

never been developed or presented until the moment of revelation.

|

|

Other writers accused Keeler of

violating

all the established tenents of mystery fiction... at least according to

Keeler's proud brag. As his style developed it was not

unusual for a character in a novel to read a diary which was then

reproduced

in full, going on for many chapters; or for two characters to meet and

begin a single conversation

which went on for many chapters, or even a substantial fraction of the

whole novel.

He was dropped by his US publisher in 1942, and by his British

publisher in 1953.

Most of his novels written after 1953 went unpublished in english except for a few

lending library editions issued by Phoenix Press; however, quite a number

of the novels

written between 1950 and 1960 saw print in Spanish and Portuguese

translation.

While much of Keeler's output could be classified as mystery and

detective fiction,

he also produced straight “thrillers” in a Keeler version of the

Edgar Wallace vein, and even some science fiction, fantasy and

historical fiction.

His very long novel, The Box from Japan (1932), could be considered

a science-fiction thriller, with intercontinental 3D TV, spies, dramatic car

chases and much more. The White Circle, written in the late 1940s for science-fiction

publisher Lloyd Arthur Eshbach but never issued by him due to

the financial collapse of his Fantasy Press company in 1950, involves time

travel via what would today be called anchored wormholes.

Keeler might be considered the first of all “bloggers,” because

of his amazing publication, The Keyhole. This was initially a one-page mimeographed newsletter,

sent out occasionally (and free) to about 100 subscribers; it contained personal information about Keeler,

and comments on various people, places and events of the day. After the death of his wife Hazel in 1960,

Keeler ceased working on new novels and put more time and effort into his Keyholes, which grew to several

pages per issue (each page a different paper color), with print runs of more than 1,000 copies.

Considering printing and postage costs of the day, these newsletters must have cost Keeler more than

$50 per issue, a very significant sum of money for the 1960s, especially given his very slim income during that period.

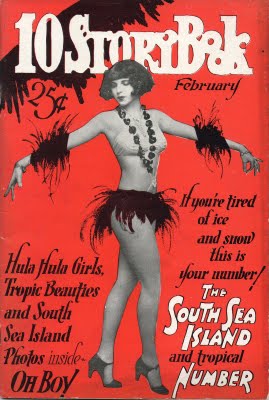

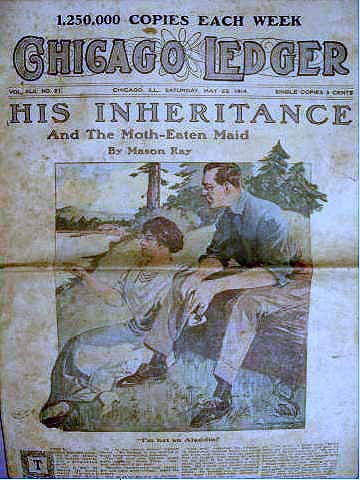

One of several pulps edited by Keeler. |

|

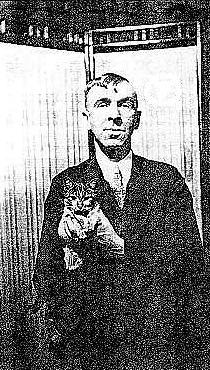

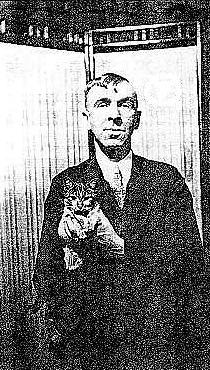

There are a number of similarities between Harry Stephen Keeler and another

of my favorite authors, H. P. Lovecraft. For example both men loved archaic or obscure words, and wrote

in a large vocabulary when allowed to do so. But most notably, both Lovecraft and Keeler had a tremendous

love for cats. No hungry and/or cold stray cat was ever turned away from Keeler's door, no matter how

low his funds at the time. His love extended pretty much to all living things, and in one of his Keyholes

he explains how he found a Monarch butterfly which had obviously “given up” and was patiently

waiting to die. Keeler brought the butterfly inside and kept it alive for days, feeding it a mixture of

honey and water and then carefully cleaning it so that it wouldn't get stuck and lose a leg.

Another literary similarity between Lovecraft and Keeler is frequent and detailed references to an

imaginary book, in Keeler's case a compendium of wise Oriental sayings called The Way Out,

in Lovecraft's case the famous compendium of forgotten and dangerous ancient lore, The Necronomicon.

At my current, advanced age (70) I don't think there is much hope that I will

be able to read all 85 of Keeler's novels, not that I would want to. However, readers who are younger and made

of stronger meat will be happy to learn that all of Keeler's literary work, including the Keyholes,

has been brought back into print by Ramble House [named for a boarding house that features in

four or five of Keeler's later novels]. This is a very small outfit which produces very attractive trade

paperback editions of the works of Keeler and other suitably strange authors. Not every book by Keeler is

available at any given time, but all titles have been reprinted at fairly regular intervals so far. Philosophy

Professor Richard Polt of

Xavier University also leads an organization devoted to Keeler and his

works. A notable Keeler scholar, familiar with all of his writings, is St. Louis University

law professor Francis M. Nevins, whose investigative skills

and persistence ferreted out much of the “lost” work of this one-of-a-kind writer.

The latest issue of a newsletter devoted to all things HSK.

This weekly Chicago paper was edited by Keeler.

Back