|

Science Fiction in Pseudoscience |  |

The term "science fiction" was invented to describe a certain genre of literature popularized in the 1920s, when pulp magazines specializing in this type of fiction first appeared. But as a category of popular literature, under no particular name, science fiction is to be found in general fiction magazines throughout the 19th Century. Many of the themes invented by writers 100 to 180 years ago have penetrated the public consciousness so thoroughly that pseudoscience writers need only mention one or two key words to suggest a whole pseudoscience scenario in the mind of the reader! What is really frightening, however, is that the average reader probably thinks these familiar concepts borrowed from nearly two centuries of fantasy fiction are actual, well-established scientific fact--- real phenomena of the real world! In fact, the vast majority of these science fiction themes are fictional cliches without any fixed meaning, much less any correspondence to anything in the real world.

Let's discuss some of the more common themes that appear in 19th century fantastic fiction. These include:

|

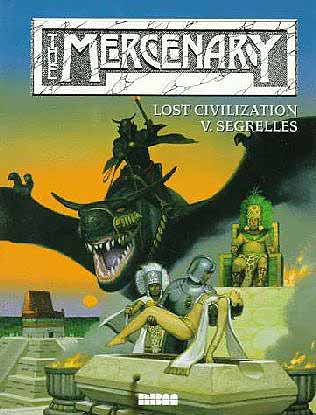

LOST CIVILIZATIONS. The usual story goes that an explorer stumbles onto a "lost" civilization in some isolated part of the world; a high urban civilization that has no contact or communication whatsoever with the rest of the world, is geographically isolated by jungles or mountains, and, often, possesses a high technology. In the 19th Century this fictional cliche, particularly exploited by British novelist H. Rider Haggard, was a pleasant enough conceit, but it makes little sense today, with the globe so thoroughly explored. Furthermore, the concept of an advanced but totally isolated civilization is contradictory, since historically the main stimuli for the growth and development of cities and civilizations have been widespread trade and frequent cross-cultural contacts. In 19th century fiction, the hero generally falls in love with the local princess and gets her out of the country just as a volcano or something similar destroys the civilization forever. |

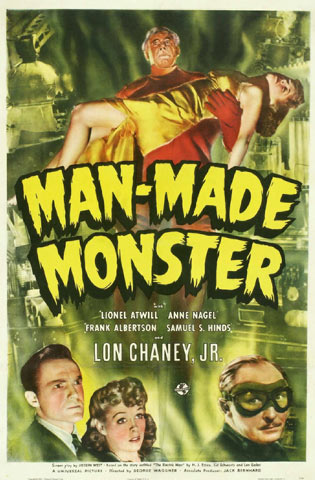

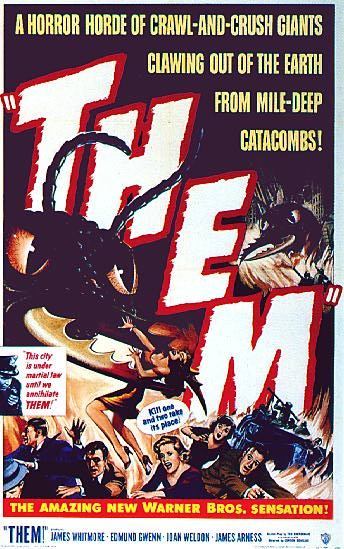

NEW ANIMALS, BOTH FOUND AND MADE. This was an especially popular theme in the latter part of the 19th century. Still-surviving dinosaurs could be found on a remote plateau in South America, as in The Lost World, by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle; familiar small animals could be made unrecognizably gigantic, as in The Food of the Gods, by H. G. Wells; or animals could be surgically turned into human beings, as in The Island of Dr. Moreau, also by Wells. Hence our inheritance of two familiar themes: those supposedly extinct animals are hiding out somewhere, and those meddling scientists can create monsters to menace us. Public fears of and legal interference with modern genetic engineering experiments, basic stem-cell research, and cloning probably stem mainly from such fantasies, not from any plausibly real threat or menace.

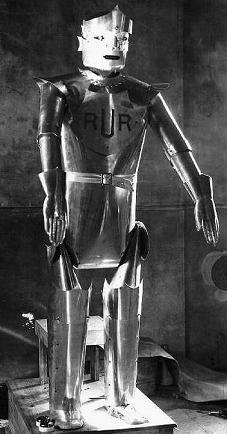

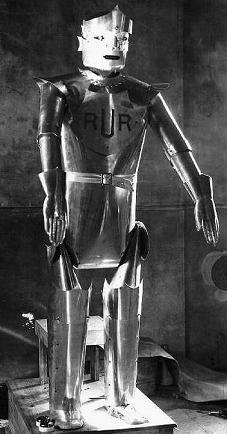

MECHANICAL LIFE— ROBOTS AND ANDROIDS. Many writers explored this theme during the latter half of the 19th century, often as a social satire on the ultimate influence of assembly lines--- assembling people rather than products. In 20th Century science fiction the terms "robot" and "android" have clearly established meanings of which movie and TV script writers and many others seem to be totally ignorant. A robot is any machine which can do all or some of the work of a man without human supervision. It's made of metal or plastic and looks like a machine, although often a machine shaped vaguely like a man. Think of the Tin Woodman in the Oz books of L. Frank Baum. An android is an artificial human; it can operate mechanically or biochemically, but it is manufactured--- and it usually looks just exactly like a real human. The concept of mechanical life grew up out of the fad for clockwork automatons that continued from the mid-18th to mid-19th century. The automaton connection is explicitly present in the Ambrose Bierce story, "Moxon's Master," in which a mechanical chess player supposedly murders its designer.

|

[19th Century clockwork automata played musical instruments, wrote and sketched. One of the most famous was Robert-Houdin's mechanical acrobat Antonio Diavolo. The most amazing might have been the 18th Century duck created by Vaucanson. It moved about, pecked, ate and flapped its wings realistically, and even excreted after eating. Try these links: 1, 2, 3, and 4. To avoid confusion, it might be noted that many of the supposed automata exhibited by 19th and early 20th Century magicians on stage were actually puppets actuated by unseen human operators. Robert-Houdin himself exhibited a mixture of actual and fake automatons. One of the most notorious of fake automatons was the mechanical "Turk" chess-player whose operation was famously figured out by Edgar Allan Poe.] |

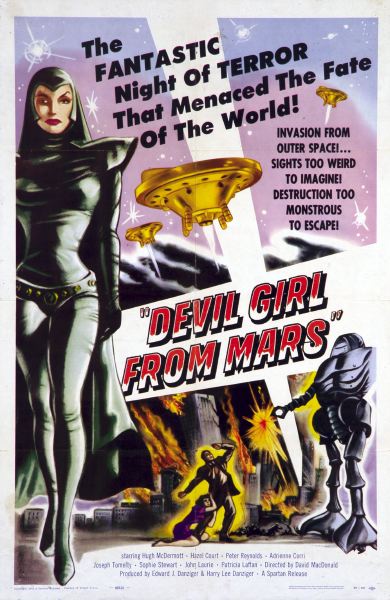

VISITORS FROM OTHER PLANETS. This is probably the single most familiar theme from science fiction. As soon as people suspected that life is a natural phenomenon, which may appear anywhere conditions are right, and that the other planets are worlds more or less like our own earth, the possibility that intelligent creatures from other planets might visit us became a common topic of discussion. Realistic speculations along these lines go back to the 1600s. Sometimes the visitors of fiction were peaceful and came to Earth seeking knowledge; other times they were desperate and/or warlike, and came to earth seeking conquest. Reality is quite different. There is no evidence whatsoever that creatures from any other world have ever visited Earth, and our increasing knowledge of the other planets of our solar system--- none of which is suitable for life--- makes clear why we haven't been visited. Visits from other solar systems are an extremely remote possibility, in view of the vast distances between stars with solar systems and the vast numbers of such systems to choose from.

|

VISITS TO OTHER PLANETS. This tradition in literature goes back nearly 2,000 years, but only in the 19th century did writers of such stories generally try to describe the other planets "realistically," as they actually were then thought to be, rather than as imaginary Cloud-coocoolands in which anything was possible. Nineteenth century fiction about visits from and to other planets had a strong influence on the 19th century pseudoscientific religion of Theosophy, and through it on much of 20th century pseudoscience. (Did you know, for instance, that the Earth was once colonized from Venus?!? Or that Atlantis had a death ray?!? Edgar Cayce knew, because he read everything written by Madame Helena P. Blavatsky! And she read a lot of early science fiction!) |

|

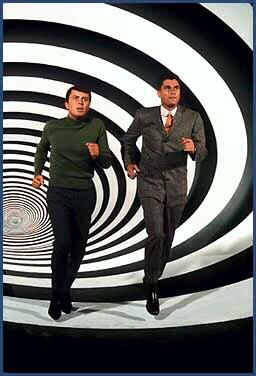

TIME TRAVEL INTO THE PAST. There is no debate, even among science fiction writers, that this is completely impossible. It not only involves violations of the laws of physics, particularly the Second Law of Thermodynamics, but literally and actually involves gross logical contradictions. The idea is that mad Dr. Soandso gets into his time machine (not clearly described) and somehow goes back to ancient Rome, where he gives a translated handbook of physics and chemistry to a Roman scholar, and thus utterly changes the course of human history--- the atomic bomb, for instance, is then invented by Claudius Festus Arpinna in 350 AD. Despite the fact that even the writers agree time trips into the past are an impossibility, they love to play with them, because of the plot complications that can be generated by the logical contradictions that arise. My favorite books of this type are Dinosaur Beach by Keith Laumer and The End of Eternity by Isaac Asimov. The time-travel short story to end all time-travel short stories is All You Zombies!" by Robert A. Heinlein. H. G. Wells' 19th Century classic The Time Machine is the genre's daddy.

|

|

|

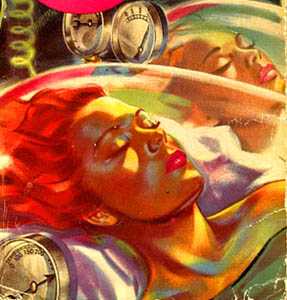

SUSPENDED ANIMATION OR TIME TRAVEL INTO THE FUTURE. Nothing impossible about this, we all travel into the future at the rate of one second per second, and a pseudoscientific rewrite of the Rip Van Winkle plot was the easiest way for a writer to get his 19th century Everyman into the Utopian future to comment, marvel, and react. A classic example is Wells' When the Sleeper Wakes. However, travel into the future (possible--- in fact, unavoidable!) is not much fun unless you can return to the past to tell the home folks what you saw (impossible). A highly technical discussion of the status of both physical and logical objections to time travel can be found here. |

|

INVISIBILITY. This theme was ever-popular in the 19th century--- Wells' novel about the Invisible Man, or Bierce's short story about a man eaten alive by an invisible animal, are typical. Again, this is a physical impossibility. In order to be invisible, an object would have to have two simultaneous characteristics, which are totally unrelated. It would have to be transparent, and would also have to have an index of refraction that is exactly equal to that of air. A transparent object (like glass or quartz) is not invisible, because it does not have the same index of refraction as air. But in fact no solid object (or liquid object) can have an index of refraction anywhere close to that of any gas at normal temperature and pressure. What is more, air does not have a fixed index of refraction-- it varies with pressure, temperature, etc. All solids and liquids have fixed indices of refraction. To show that the idea of invisibility involves practical contradictions, imagine an invisible boat. A transparent boat with the same index of refraction as water would be clearly visible in air (as is a splash of water), and thus invisible only below the water line. If we instead made it have the index of refraction of air, the part below the water line would be clearly visible (like an air bubble in water). Also, a boat made of a transparent material, like glass, would not be too seaworthy! In the laboratory, or even the kitchen, one can find liquids which have the same index of refraction as certain glasses. If a piece of such glass is completely immersed in such a liquid, it cannot be seen (although it would easily be felt by putting one's fingers in the liquid)--- but it would show up on radar or sonar. This does not seem too practical from a military standpoint!

Note also the following: in general, there is no way to "make" a material become transparent that is not ordinarily transparent. Transparency is a more-or-less intrinsic property of objects, determined by the way the atoms or molecules of the object are bonded to one another. A final comment: an invisible creature would also be blind! Eyes work by absorbing light. More on invisibility can be found here.

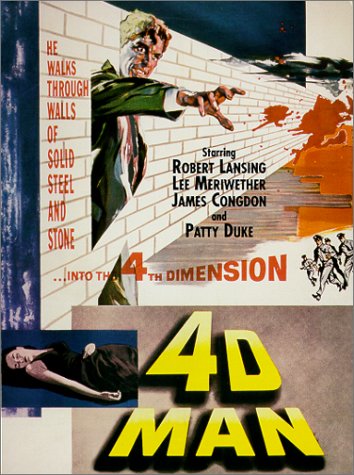

THE FOURTH DIMENSION. The general claim is that there are "other" space dimensions, somehow at right angles to the three we know, and if we could just "learn" to move in these other dimensions (usually only one other, the fourth) we could do apparently supernatural things, like instantaneously travel from one spot to another, penetrate solid through solid (walk through walls), etc. The fact that all forces whose ranges are not otherwise limited fall off with distance exactly as the inverse square, to a very great measured accuracy, indicates directly that there are no more than three space dimensions available to matter and to forces-- and everything in the universe is made of matter and acted on by the same four fundamental forces. Physicists and mathematicians routinely work in abstract spaces of arbitrary numbers of dimensions, even infinite numbers of dimensions. Further, modern efforts to unify the electromagnetic, weak, and strong nuclear forces, which are understood quantum physically, with gravity, which is today still understood only classically, sometimes involve working with many actual space dimensions, 9 or more. This is, so far, a mathematical technique to make a probably incomplete theory generate possibly realistic numbers, and has nothing to do with the observed number of space dimensions. In these approaches, variously called string theories, supersymmetric theories, or superstring theories, all higher dimensions have to be made compact, curled up on themselves, so that particles cannot move or forces propagate along them, otherwise the theories would not work at all! At present, these ideas are just things for physicists to toy with until they find a convincing quantum theory of gravity, and have no particular physical significance. More on "higher dimensions" can be found here.

|

An obvious comment is that if actual higher dimensions did exist, nothing could readily prevent matter, forces, or us from moving in those directions to begin with, and we would know about them from the beginning, just as we know about forward, sideways, and up.

COEXISTENT WORLDS. These are usually confused by pseudoscientists with the fourth dimension and parallel worlds, two totally unrelated ideas. The original 19th Century fantasy fiction theme of coexistent worlds is that since we see only a very limited part of the full electromagnetic spectrum, maybe there are features of the world of which we are unaware--- for instance, if we could see by ultraviolet light, why maybe New York City would also be a jungle! We wouldn't be aware of the jungle since it can be seen only in ultraviolet light. There are thematic hints of such ideas as far back as pre-Socratic Greek philosophy. If such claims makes sense to you, you may have a lot to learn about nature. In each of the last three themes, writers almost always confuse "invisibility" with "intangibility." A blind man can't see the curbstone, but that doesn't prevent him from tripping over it! An object which could not be seen could still be felt, and its existence would be obvious! Furthermore, an object which reflected only ultraviolet light, for instance, would be clearly visible. Why? An object which does not reflect visible light appears black to our eyes. A jet-black tree is just as visible as a regular tree, at least in the daytime.

VIBRATIONS. Physicists in the 19th Century were very interested in vibrations and waves. Writers of popular fiction, and pseudoscientists, took only these words, and used them as vapid buzzwords. (A buzzword is a word which is meaningless in its context, and usually is applied too broadly to so many things that no meaning could possibly be assigned to it in its customary "non-scientific" applications.) Thus writers started saying things like "everything is made of vibrations, and the only difference between one thing and another is the rate at which each vibrates, its frequency. If I could change my vibration rate to that of platinum metal, I would become platinum metal." This is the 19th Century origin of the familiar 20th century buzzword "vibes." "The vibes are not right today for me to do this job. Think I'll puff some boss weed instead!" It makes no more sense to say that things are "made of" vibrations than it does to say they are made of "sidewise motions" (what is moving?) or that they are made of "temperature" (what has the temperature?). Matter is made of atoms. Atoms may or may not "vibrate" in a loose, quantum-physical sense which is nothing like classical vibration, but is more like superposition of two or more different states; it's always the atoms and their properties that are important.

ENERGY. Late Nineteenth century physicists were also extremely interested in the concept of energy. In physics, "energy" is a bookkeeping device for keeping track of the amount of work that has been done on or by a system. In popular fiction, energy became a buzzword, and finally a kind of substance. Science fiction writers and pseudoscientists today talk about things made of "pure energy." Since the temperature of a system, for instance, is a direct measure of the average internal kinetic energy of a single particle in the system, to say something is "pure energy" makes no more sense than to say something is "pure temperature." This is pure gibberish, without any connection to the world we live in. Energy is not a substance or a thing. It is a number (with units of work) and it is not the number of anything. That is, the number is arbitrary! "Energy" is by far the most overwhelmingly popular of current pseudoscience buzzwords. There is probably not a single example within all of pseudoscience where the word "energy" is used correctly, accurately or descriptively! The word energy was adapted into physics from an ancient Greek term, by Thomas Young in 1807 and subsequently extended and popularized by James Joule in the mid 1800s, to describe the purely abstract physics concepts he had defined and was then studying. It is important to realize that when pseudoscientists talk about "energy" ideas of the ancient Chinese or Mayans or Bareassians or whoever, the word they are mistranslating as "energy" invariably means air, wind, breeze or breath! There is no equivalent to the concept of energy in physics existing and present in any culture anywhere, before it was introduced by Young and Joule.

|

|

|

PARALLEL WORLDS. Another ever-popular idea from 19th century fiction was, "what if?" What if the South had won the Civil War? What if Napoleon had not invaded Russia? Characters were struck by lightning or something and woke up in another world in which history had taken some other turn. It makes for a good novel, but it has nothing to do with the world we live in. In its purest form, this is a naive "concrete" interpretation of the abstract concept of probability--- the claim that if the coin is 50% likely to fall heads, and 50% likely to fall tails, it has to do both--- the universe splits into two universes, in one of which the coin falls heads, in the other of which it falls tails. Since almost everything that happens in the universe is a matter of probability, and since an almost limitless number of processes are taking place in each split second, one is talking about an almost limitless number of new universes being born every split second. Of course, one can talk about anything. |

There is, however, nothing in the real universe we can see that corresponds to the concept of parallel worlds. In modern physics one does encounter what are called "multiple vacua." The present state of the universe is not the only possible state. For all we know the whole universe could suddenly make a phase transition (like the transition from solid to liquid) to a different vacuum, in which all the fundamental constants and laws of nature would be totally different, and all things as we know them would cease to exist. John Taine's 1926 novel Green Fire describes something like that. But such a possibility has nothing whatsoever to do with the concept of parallel universes, which are instead more often confused with higher dimensions, coexistent worlds, etc., etc. A good 20th century science fiction novel dealing with parallel worlds is Keith Laumer's Worlds of the Empirium; see also H. Beam Piper's classic Paratime series. Murray Leinster's 1934 short story “Sidewise in Time” is usually credited with introducing the concept of parallel words into mainstream science fiction.

DETACHABLE "MIND." What if we could transfer your mind into the body of a spider? Or my mind into the body of a whale? Makes for a good 19th or 20th century fantasy story or satire, but what on earth are we talking about? Not brain transplants. Some swami makes a mumbo-jumbo incantation--- the 1980s movie All of Me features a classic example--- and minds shuffle around among bodies like cards. What does the word "mind" mean anyway? What the writers did is to take the ancient, referentless religious concept of the soul, rename it "mind," and go on from there. Again, there's no connection to reality at any point. But it's now a common teaching in pseudoscience that you can "learn"--- there's that word again, and it's just $250 for easy lessons if you act today!--- to detach your mind from your body and send it out to visit distant places. Sounds like a primitive scenario to account for the very natural phenomenon of dreaming.

REALITY AS MENTAL IMAGE. Another theme of 19th century fantasy fiction was to have a character realize that his inner thoughts could reshape the whole universe-- by thinking that everyone should have two heads, he somehow causes everyone to instantly and from then on have two heads. H. G. Wells wrote a fine story along these lines, entitled "The Man Who Could Work Miracles," and 20th century writers have used it too, such as Ursula LeGuin in The Lathe of Heaven.

As far as reality is concerned, however, it is one of the most obvious facts of our experience that the universe goes on totally independent of our thoughts, desires, dream, and fancies. The fact that a dimwitted cook doesn't know or remember what temperature water boils at, or thinks water boils at 50° F, does not alter the boiling temperature of the water on the cook-stove. The original 19th century nonsense has been re-treaded many times, and most recently has shown up in crackpot cultic popularizations of quantum physics or in books about "mystical physics," in which it is claimed that physicists have shown that "your mind creates your own reality," and similar vague gobbledygook. In recent decades the pseudoscience/cult of manifesting has become a particularly dismal exploitation of such garbage-- want to become rich? Just want to be rich “hard enough” and you will create the new reality in which you are rich. Seems simple enough that the entire population of the earth should now be rich, instead of just that notorious 1 percent! In the harsh reality we actually live in, what goes on in the human brain has no more effect on what goes on inside the nearest star than what goes on inside the nearest star immediately has on what goes on inside the human brain. How various processes affect one another is the precise thing that physicists do study. There is no question, experimentally, that thoughts alone do not affect processes going on outside the body.

CIVILIZATION AS PERIODIC. When in the late 19th century people began to realize the earth was millions of years old (actually it's billions of years old), but knew little or nothing about biology and evolution, they said things like, "But recorded history only goes back a few thousand years! What were humans doing the rest of that time?" In fact, of course, humans didn't even exist for most of earth's history, as was clearly understood by the end of the 19th century. But writers and pseudoscientists were going strong with the theme of civilizations rising and falling, rising and falling. Half a million years ago some great civilization had TV and microwave ovens and girls who could kick off all their clothes even faster than the latest movie starlet. But that civilization fell, and humans reverted to savagery, and then a long climb began up to our present civilization, which will also fall, etc. There is no question but that this idea is totally wrong as it applies to the past. There is not one shred of archaeological evidence of any past civilization with a technology anything like our own. The archaeological record is wholly consistent with the usual idea that urban civilization is only about 10,000 years old at most. (The human race itself, in its present form, is only around 50,000 years old, and for most of its existence lived a semi-nomadic, hunter-gatherer lifestyle.)

|

WE'RE PROPERTY. If there were creatures on other planets that were much more advanced than we are--- a very familiar idea in the 19th century--- then,they might not even consider us intelligent, much less civilized. Maybe they consider us like domestic animals on a farm--- or like exhibits in a zoo! Maybe they own us, tend us secretly, cull out fat specimens and eat them. Lots of good stories have been written about this, and early 20th century pseudoscientist Charles Fort got more than one book out of the theme. But alas, there is no evidence whatsoever of visitors from other planets, advanced or otherwise, benign or malevolent. The other problem is why visitors from other planets should have any attitude toward us at all, pro or con. What's your attitude toward the squirrels in your back yard? Or the ants? Or the crickets? If they don't bother you, you probably don't even notice--- much less bother--- them. And they're right in your backyard, not 100 light years away. |

|

Early 20th century science fiction writers did not add that many new themes. The four most often encountered are:

|

THE ATOM AS A LITTLE SOLAR SYSTEM--- OR, OUR SOLAR SYSTEM AS A GIGANTIC ATOM. This is based on a public misunderstanding of very early, primitive work on the structure of the atom. In Bohr's early, pre-quantum model, electrons orbit the nucleus of the atom vaguely as planets orbit the sun. But this picture of the atom is not correct. An atom is absolutely nothing like a solar system; electrons are absolutely nothing like planets. The classical physical laws obeyed by planets are totally different from the correct quantum-physical laws obeyed by atoms and their constituents. This is a fine instance of a completely false analogy. The classic story in the genre of atoms as solar systems is Edison-collaborator Ray Cummings' The Girl in the Golden Atom. And, if you wonder why there's so little hope for K-12 science education in the US, here's a concrete example of why hope has fled! But check out the Simpsons' version of the classic film Powers of Ten for more inspiration. |

|

|

MATTER TRANSMITTERS. I don't know who invented this concept, but it was probably Ralph Milne Farley in the 1920s with his RADIO MAN series. The idea is familiar from the later use in TV fantasy shows like STAR TREK. Somehow your body is scanned and recorded--- and in the process presumably inevitably completely destroyed! Then the information is transmitted some vast distance and the body reconstructed somehow from the information available, using raw materials lying around in the new location. |

That this is not just difficult but essentially impossible can easily be seen. There are about 1028 atoms in a human being. Suppose that the position of each atom could be measured in about the time it takes light to cross an atom--- that is as fast as it could possibly be done, assuming the measuring device literally peels away the body and so is literally in contact with each atom it measures. The time for light to cross an atom is about 10-18 seconds. So to scan a human body would take about 1028 x 10-18 sec or 1010 seconds, or about 300 years! To reconstruct the body at the other end, again as fast as possible, would take the same length of time. Furthermore the reconstructed body would be just that--- it would not be the original individual who was destroyed more that 6 centuries before, at the other end of the transmitter. Any activity of the brain that involves living, dynamic behavior--- unsteady currents, makes and breaks of contact, etc.--- could not get recorded. In fact, keeping the scanned corpse intact for 3 centuries would be a major task in itself! Only information stored in the form of specific molecules would get across. In short, even if the scan were done by magic, rather than science, and thus took only seconds, the reconstructed body might have some of the (molecular-based) memories of the original individual, but should not have all of his personality, training, etc.--- or possibly any of it. Algys Budrys' novel Rogue Moon (republished as The Death Machine) actually turns on this specific point.

SPACE WARP, HYPERSPACE, STAR DRIVE, HYPERDRIVE, WORMHOLES: Interstellar travel is not too practical a prospect, because to travel any significant fraction of the radius of our own galaxy would require thousands of years travelling as fast as one can go, just under the speed of light. Science fiction writers have invented various totally imaginary ways to get around this problem so that they can use the usual cowboys and Indians plots. You can't rescue Princess Layya from Barf Tater if it takes 300 years to find out he has her and 400 years to get to where she's held prisoner. Layya and Barf would presumably be long gone by the time Luke Starkicker got on the scene with his faithful robot companion DO-2-U-2. Apparently the first writer to consciously avoid this problem was E. E. (Doc) Smith, back in the 1920s--- probably because he was also one of the first writers to do much with the concept of interstellar travel, in his famous Skylark and Lensman series. "Doc" solved the problem by asserting that his space ships could be made inertialess--- and thus (according to "Doc," who in the real world was an expert in the chemistry of doughnuts) could in their inertialess state travel effortlessly at huge multiples of the speed of light. In fact, however, an object without inertial mass (for instance a photon!) must travel at precisely the speed of light, neither faster nor slower, at all times. "Doc," for purposes of his stories, was also unclear about how one "goes inertialess," since inertia is an intrinsic property of matter. It's a shame old "Doc" is not often read today; his stories are the pure essence of late 1920s-early 1930s science fiction.

Later writers sought to avoid these and other problems with physical law by literally writing their way from one star to another; that is, by cloaking the problem with a "solution" of swell-sounding gibberish terms. The standard solution is that the space ship somehow enters an alternate universe (aka hyperspace) where almost infinite speeds are possible. Terms like hyperspace and space warp, common in science fiction literature since the 1930s, have become familiar recently to hundreds of millions of illiterates via their use in fantasy TV shows and movies involving interstellar travel. Anyway, the space ship "makes the jump to hyperspace," or warps space, and then when it gets near (?) its destination (?)--- how it navigates, and through what, is unknown and unspecified--- it comes back into "regular space." Now, this is all total and absolute garble, with no connection to the real universe in which we live. Even considered as an abstract scenario, it contains internal contradictions. Why should there be any relation between position in hyperspace to position in real space? Just moving straight up into the air ("making the jump to the third dimension") doesn't get you from Rome to Buenos Aires. Indeed, the entire concept of dimensions is based on the fact that motion along one dimension is independent of motion along any other dimension! And how does one go into hyperspace... or warp space... or construct a star drive that "clutches at the very fabric of space itself?" The writer, at his typewriter or computer, has no troubles. He can make up any convenient rules he wants, however inconsistent. But in our real universe the rules are not so flexible. The fact remains, if you want to go from one point in the universe to another point, you cannot go at a speed faster than 186,000 miles per second, period. You can, of course, go much slower!

Recent science fiction writers frequently replace the meaningless buzzwords "space warp" or "hyperspace" by wormhole, which in the context in which they use it is equally meaningless. The word "wormhole" actually does refer to something in physics, namely a certain physically meaningless solution to the field equations of Einstein's classical theory of gravitation... but the word does not refer to anything in reality. Thus, it is just one more totally imaginary way to ignore (on paper) the nearly insoluble problem of interstellar travel.

ESP, PSYCHIC POWERS, PSIONICS. Two themes became so immensely popular in the 1950s that they almost completely dominated science fiction for more than a decade. The first theme was the aftermath of a global thermonuclear war, with a world sunk back into savagery and inhabited by weird, dangerous mutants. The second theme was the awakening of fantastic, generally godlike human mental powers. This latter theme has been so popular that fiction writers, movie and TV scripters, pseudoscientists and newspaper reporters tend to forget that no such powers have ever been demonstrated in any real laboratory inhabited by real scientists. Popular fiction from the very first has been full of mysterious individuals with supernatural powers--- the same powers possessed by the gods themselves in the various mythologies associated with the world's popular religions. In the 19th century, two new religions, Spiritualism and Theosophy, summarized conveniently, and named or renamed, the powers that the gods would have, but that we poor humans never seem to possess. These powers include the ability to read minds, telepathy; the ability to foresee the future, precognition; the ability to "see" what is behind windowless walls and within locked drawers, clairvoyance; the ability to move or alter objects without touching them, by sheer "mental force," psychokinesis, or telekinesis; the ability to cause oneself to vanish at one spot and instantaneously appear at another, teleportation; the ability to "take over" another's body, animating it and "looking out through" its eyes and other senses, possession; and so on. As has been pointed out many times, the only thing these imaginary powers have in common is their tendency to recur in the daydreams of frustrated adolescents. "If I could only... I wish I could... Boy, if I could just...." Pretending that such powers really do exist, although we of course don't have them yet--- or rather we aren't trained-- is purely and merely wish fulfillment, of a rather pathetic kind. In the 1930s, the catchall term ESP (Extra-Sensory Perception) was adopted for all these powers, a rather poor name since most of them don't involve perception. Thus science fiction writers introduced another term, psi powers. The imaginary science of such powers was then called "Psionics." People with ESP were called "esp-ers" and so on.

The two themes of post-nuclear war and psi powers sometimes blended, as in stories where imaginary mutants created by peacetime or wartime radiation developed such powers. Or the human race was depicted as evolving toward such powers. Indeed, a standard science fiction picture of a highly advanced or highly evolved race, since the 1930s, give them not only the physical but also the mental powers attributed in mythology to the gods themselves. This saves any necessity for the science fiction writer to exercise any imagination or originality, regarding what an advanced species would really be like.

SCIENCE FICTION AND RELIGION: It's not often appreciated how great an impact early science fiction has had on some well-known religions that developed in the past two centuries. Among them are Mormonism (circa 1830), Theosophy (1875) and Scientology (1950). It's well-known that the Book of Mormon incorporates an unpublished science-fantasy manuscript by Solomon Spalding. Madame H. P. Blavatski incorporated almost all the science-fictional themes current in 1875 into her wild synthesis of Theosophy. And L. Ron Hubbard was an established writer of pulp science fiction and fantasy when he put fiction aside to invent Dianetics and Scientology.

IN CONCLUSION: The great danger of all the things we have discussed here is that some people will tend to accept everything that appears in works of fiction, no matter how far fetched, as somehow "real," as if the authors of the stories have no imaginations, no tradition of fantasy and religious themes to draw on, and no ability to invent things of their own. Science fiction is in no way science fact; it is a literature of entertainment, not of instruction. There is little or no science involved in the usual science fiction story, which since the 1950s has anyway turned increasingly on political and social issues. Even the handful of writers who did know a little or a lot about science--- such as Hal Clement, Poul Anderson, and Arthur C. Clarke--- would always ignore unpleasant facts if they get in the way of the plot or the characters. Any fiction writer is out to interest you, then to entertain you and amuse you. He does not try to function as a scientist or as a teacher; he does not feel any obligation to depict the actual universe in which we live, and generally he does not depict such a universe.

Sadly, pseudoscientists regularly take advantage of public familiarity with the common themes of science fiction, just as they regularly take advantage of the public's ignorance of most real scientific facts and authentic science discoveries. Over the past decade, reports in the press of what is often legitimate scientific work have often referred to that research in terms of science-fictional themes, which has not helped the state of total confusion that generally exists. Thus, abstract studies of Einstein's theory of gravitation are often reported as "the quest for a time machine," while experiments in recording states of simple quantum systems are referred to as "quantum teleportation," and so on. Scientists themselves will (very unwisely) on occasion use terms from science fiction or fantasy in discussing various speculative ideas in physics, from “parallel universes” to “invisibility cloaks.”

For further reading---

Links---

Acknowledgments--- Dr. Rory Coker, Professor of Physics at the University of Texas at Austin, is the author of this fact sheet. The International Cultic Studies Association, a professional research and educational organization concerned about the harmful effects of cultic and related involvements, prints and helps distribute these fact sheets. Because such fact sheets seek to stimulate critical thinking, rather than advance a particular point of view, opinions expressed are those of the authors. These fact sheets may be copied, translated, and disseminated in various forms for educational purposes, but they may not be reproduced for resale.